The Seven Types of People in Evil Systems

Evil systems are not sustained by villains alone. Ordinary people play a far larger role than they'd like to admit.

“It is chiefly in times of physical, political, economic, and spiritual distress that men’s eyes turn with anxious hope to the future, and when anticipations, utopias, and apocalyptic visions multiply.”

Carl Jung made this observation in 1957, having lived through the creation, sustainment, and collapse of totalitarian systems. It is a sharp insight: before societies impose systems of total control, there is often a widespread psychological disorientation—an erosion of moral confidence, judgment, and shared reality.

No matter whether you’re left, right, centre, or determined to avoid politics altogether, most people sense that we are standing on unstable ground. We haven’t merely argued ourselves into confusion or grown more hostile in public debates. A more accurate description is that something deeper has shifted. People seem… spellbound.

As personal, social, and economic conditions worsen, populations become more receptive to collectivist promises—tempted to trade freedom for comfort and certainty. Fyodor Dostoevsky captured this bargain with chilling clarity through the figure of the Grand Inquisitor in The Brothers Karamazov:

“In the end they will lay their freedom at our feet, and say… ‘Make us your slaves, but feed us.’”

This is the pitch at the heart of every totalitarian movement: order, bread, and moral certainty. In times of anxiety and dislocation, the offer is profoundly seductive. Dostoevsky warned that “anyone who can appease a man’s conscience can take his freedom away from him.”

From Bolshevik and Maoist revolutions to Iranian theocracy and European fascism, the pattern repeats. Different symbols, different enemies—but the same psychological mechanics. A small cadre of psychologically disordered revolutionaries promises utopia, while large numbers of otherwise normal people—confused, fearful, and morally exhausted—are drawn into movements that offer certainty in place of responsibility.

This is where the work of psychiatrist Andrew Lobaczewski becomes indispensable. Having lived under communist rule in Poland, he concluded that totalitarian systems are not primarily ideological failures. They are psychological takeovers—marked by the systematic elevation of disordered personalities into positions of power, and the gradual reorganization of society around them.

Dostoevsky named the temptation and the sales pitch; Lobaczewski explains the mechanism. But neither he, nor Jung, nor Dostoevsky believed that totalitarian systems emerge simply because a tyrant imposes his will on a passive population. The darker truth they each circled, in different ways, is that such systems require participation.

In this sense, totalitarianism is not imposed so much as it is accepted. It is a deal with the devil—made not because people are evil, but because they are afraid, disoriented, and searching for relief. Understanding that bargain is the first step toward understanding how free societies quietly consent to their own inversion.

The Missing Lens

It is often useful to analyze political systems through the lenses of political science, economics, and ideology—focusing on what systems claim to do. But these frameworks routinely fail to explain something more unsettling: why certain systems behave in profoundly inhuman ways, and why the same kinds of people reliably end up running them.

Marxism, fascism, and theocracy are typically understood as economic arrangements, belief systems, or struggles for power. Those descriptions are not wrong—but they are incomplete. They cannot account for the surreal cruelty, the obsessive lying, the inversion of moral language, or the way radically different movements produce eerily similar outcomes.

Why do systems that promise liberation, justice, or salvation so often converge on repression, fear, and brutality?

Andrew Lobaczewski’s work helps answer these questions. Born in 1921, Lobaczewski grew up in rural Poland, served in the underground resistance during Nazi occupation, and later lived under Soviet-imposed communism. His family estate was confiscated by the regime. He did not study totalitarianism from a safe historical distance, but from inside societies that had been psychologically reorganized.

Lobaczewski was not primarily interested in whether one ideology was better than another. He asked a different question altogether: what kind of people rise to power under certain conditions, and how do normal people become reorganized around them?

From this inquiry emerged his discipline of political ponerology—the study of how evil arises in political systems, understood not morally, but psychologically. While evil is often treated as a religious concept or a metaphysical abstraction, Lobaczewski approached it as something observable, patterned, and diagnosable. Moral language tells us that something is wrong; ponerology explains how it takes hold.

Every society contains a small percentage of psychologically disordered individuals. Under healthy conditions, they remain marginal. But as social stress rises and moral clarity erodes, rational judgment weakens, emotional thinking dominates, and pathological traits begin to gain social traction. Carl Jung warned that when collective emotion overwhelms reason, “a sort of collective possession results which rapidly develops into a psychic epidemic.”

Jung estimated that for every manifest case of insanity, there are ten more latent cases—individuals who appear outwardly normal but whose thinking is influenced by unconscious distortions. Lobaczewski recognized that during periods of collapse and uncertainty, such individuals begin to cluster, network, and gain influence, while healthier personalities retreat, adapt, or are pushed aside.

This initiates a destructive feedback loop. Social hardship increases psychological instability; instability elevates pathological actors; pathological leadership deepens social hardship. Over time, a process of negative selection takes hold: competent and ethical individuals are removed or sidelined, while disordered personalities are promoted and celebrated. As institutions—from education and media to politics and culture—undergo this inversion, language itself is reshaped to normalize the abnormal.

The goal, then, is not to argue over what people believe, but to understand who is attracted to power under these conditions—and why. Communist, fascist, and theocratic nightmares are not sustained by a single tyrant alone, but by a recognizable cast of psychological types, each playing a predictable role in the maintenance of pathocratic systems.

1. The Psychopaths

Type: Apex operators

Driver: Power and domination

Tool: Coercion, intimidation, leverage, violence

Danger: Ruthlessness without conscience

Failure mode: Overreach, cruelty, and paranoia

Psychopaths do not merely behave badly; they experience reality differently. They see the world as something that owes them—status, power, pleasure, or dominance—and they feel no internal restraint about how those things are obtained or preserved. Terror, torture, murder, and mass extermination are acceptable tools when conditions allow. When they do not, reputational destruction, career annihilation, and social exile work just as well.

To the psychopath, life is a zero-sum contest. Morality, tradition, religion, and virtue are not guiding principles but naïve illusions. The world they envision is not one ordered by justice or restraint, but one in which they sit unchallenged at the top.

This is why their language so often mimics moral concern. Words like freedom, liberation, equality, and utopia are useful not because they mean anything to them, but because they move others. Moral language is something psychopaths deploy, not something they feel. It is not a standard they hold themselves to, but a weapon used to control those who still possess a conscience.

Importantly, psychopaths are rarely the charismatic, idealistic figures who ignite revolutions. They rise after the chaos has done its work. They wait for institutions to weaken, for rivals to exhaust themselves, and for principled people to withdraw in disgust or despair. Where ideologues start revolutions, psychopaths consolidate and complete them.

By the time they rule, cruelty has become procedure, conscience has been engineered out, and power no longer needs to justify itself. The system works—because it has been emptied of anything that would stop it.

Historical examples: Joseph Stalin, Lavrentiy Beria, Heinrich Himmler, Ali Khamenei, Saddam Hussein, Pol Pot, Augusto Pinochet.

Pop culture analogues: Emperor Palpatine (Star Wars), Littlefinger (Game of Thrones), Dolores Umbridge (Harry Potter), Ozymandias (Watchmen), Logan Roy (Succession), Agent Smith (The Matrix).

2. The Schizoids

Type: Ideological engineers

Driver: Order through abstraction

Tool: Totalizing systems, utopian logic, rationalization

Danger: Suffering justified as necessity

Failure mode: When theory collides with human reality

If psychopaths ultimately control the system, schizoids are the ones who design it. By schizoid, Andrew Lobaczewski does not mean schizophrenia, but a personality structure marked by emotional distance, weak empathy, and a powerful capacity for abstraction. Schizoids live primarily in the realm of ideas. People are not encountered as persons, but as variables. Moral concern exists, but it is conceptual rather than felt.

Their function within a pathocratic system is to supply justifying narratives, moral abstractions, and totalizing frameworks that make domination appear necessary—even virtuous. They are not typically the ones who carry out violence. Their role is more subtle and far more dangerous: they make violence thinkable. As psychopathic rulers grow increasingly cruel, schizoids supply the explanations. They construct elaborate visions of a future utopia—one that will allegedly emerge once the revolution has finished its work and resistance has been eliminated.

Lobaczewski observed that carriers of this personality structure tend to be hypersensitive and distrustful, while paying little attention to the emotional reality of others. They gravitate toward extreme moralizing positions and often display a readiness to retaliate for perceived slights. In their writings and rhetoric, a recurring theme appears: that human nature is fundamentally defective, and that order can only be imposed by a strong authority guided by exceptionally rational minds acting in the name of a higher idea.

This is the critical inversion. When the system fails, it is never the theory that is blamed. It is the people. The idea remains flawless; humanity must be corrected to fit it. Suffering, in this framework, is not a warning sign but a necessary stage of implementation.

Schizoids provide the vision. Psychopaths eventually take control of the machinery built around it.

Historical examples: Karl Marx, Mao Zedong, Leon Trotsky, Herbert Marcuse, Michel Foucault, Vladimir Lenin.

Pop-culture analogues: The Architect (The Matrix), Ozymandis (Watchmen), Thanos (Avengers), Ra’s al Ghul (Batman), Sister Sage (The Boys)

3. The Spellbinders

Type: Charismatic translators

Driver: Influence, approval, narrative dominance

Tool: Moralized language, emotional framing, identity formation

Danger: Mass manipulation through sentiment rather than truth

Failure mode: Narrative collapse when contradictions become visible

If psychopaths run the organization and schizoids design the system, spellbinders are the sales force. They take abstract ideology and translate it into emotionally contagious language. Their skill is not argument, but linguistic seduction—using words to bypass conscience rather than persuade reason. Spellbinders are neither architects nor apex predators. They are translators, capable of making cold systems sound humane and moral.

In practical terms, they function as propagandists—but not merely in the narrow sense of officials delivering speeches from behind podiums. Spellbinders operate wherever language shapes perception. They make art serve ideology. They intuit audience psychology. They excel at emotional framing, knowing which words soothe, which inflame, and which confer moral legitimacy. Their power lies in tone, cadence, and narrative, not in evidence.

Their primary tool of persuasion is emotional alignment, not truth or logic. One of their central functions is the creation of collective identity. Spellbinders ensure that everyone knows what the group is supposed to think, feel, and signal about every issue. Belonging is rewarded; deviation is marked. Moral consensus becomes social currency.

The spellbinder’s playbook is consistent: repetition of moralized language, erasure of complexity, elevation of compliance as virtue, and demonization of dissent as danger. In fiction this is often depicted as hypnosis, but in reality it is something more mundane and more powerful—emotional induction, reinforced socially and institutionally. This is how crowds come to experience themselves as righteous while actively defending cruelty.

In this sense, spellbinders are the emotional lubricants of the system. Schizoids design it. Psychopaths operate it. Spellbinders are the ones who convince everyone else that it is good.

Historical Examples: Joseph Goebbels, Edward Bernays, Pravda, Walter Duranty.

Pop Culture Examples: Varys (Game of Thrones), Stormfront (The Boys), Nick Naylor (Thank You For Smoking)

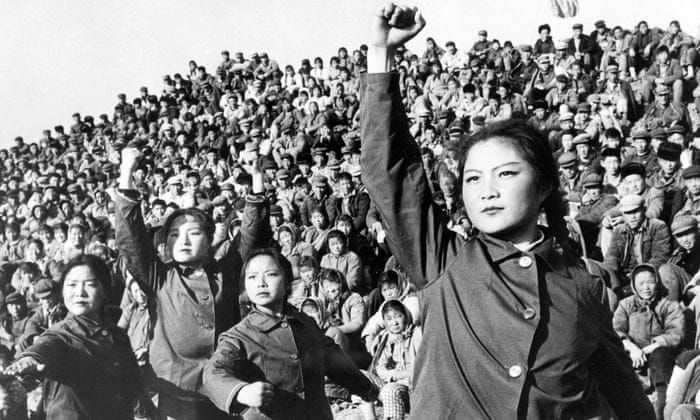

4. The Spellbound

Type: True believers

Driver: Moral certainty

Tool: Social enforcement

Danger: Scale and sincerity

Failure mode: Collapse when reality intrudes

Beneath every totalitarian system lies a mass of people who internalize the lie and enforce it on one another. These are not monsters or masterminds, but ordinary individuals who become active defenders of pathological regimes. The moral certainty supplied by the system gradually overrides independent judgment, until conscience is no longer consulted at all.

The spellbound are not psychopaths, nor are they cynical manipulators. They are sincere believers. This distinction is crucial. They do not pretend to believe—they believe. Andrew Lobaczewski described them as individuals psychologically inducted into a pathological worldview, who experience a sense of moral elevation through compliance. Obedience feels righteous. Alignment feels good.

If spellbinders create the moral language, the spellbound absorb it wholesale. They consume the movement’s slogans until belief becomes identity. The group then reinforces that identity by rewarding every visible signal of ideological conformity and punishing deviation. At this stage, enforcement becomes horizontal. Fear of exclusion replaces fear of the state. Neighbours, colleagues, classmates, and even family members begin to do the work the regime no longer needs to do itself.

This is what makes the spellbound so dangerous. Psychopaths harm through power. The spellbound harm through scale. Their numbers overwhelm reason. Once a crowd descends, no individual conscience remains to negotiate with.

If schizoids imagine the system, psychopaths operate it, and spellbinders sell it, then the spellbound are the ones who enforce it—loudly, sincerely, and in vast numbers.

Historical examples: Hitler Youth, Red Guards, Free German Youth, Blackshirts, child soldiers.

Pop-culture analogues: The Faith Militant (Game of Thrones), Inquisitorial Squad (Harry Potter), TVA Agents (Marvel)

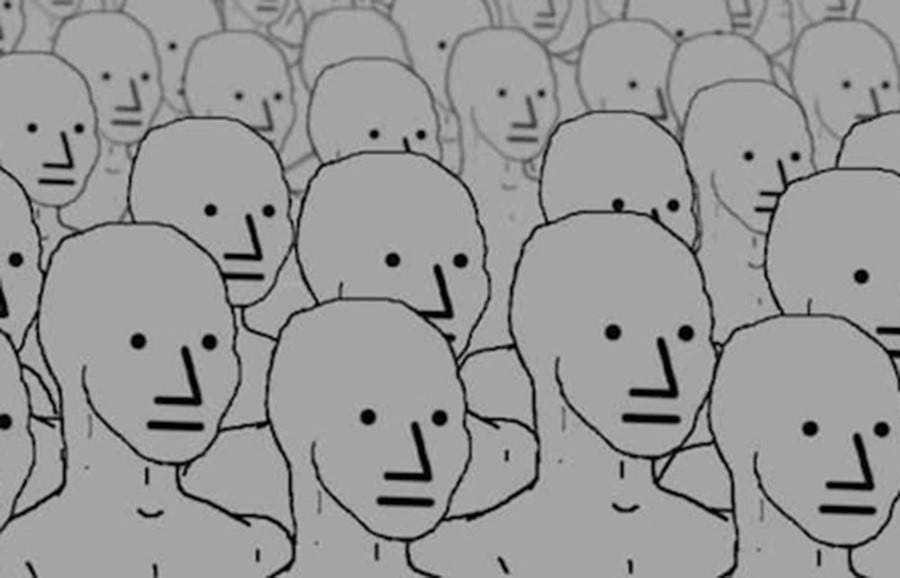

5. The Adapted Conformists

Type: Silent enablers

Driver: Fear and self-preservation

Tool: Compliance and silence

Danger: Legitimization and continuity

Failure mode: Moral numbness

If schizoids imagine the system, psychopaths run it, spellbinders sell it, and the spellbound enforce it, then adapted conformists normalize it. These people are not psychopaths, zealots, or propagandists. They are ordinary, rational individuals who recognize that something has gone wrong—and adapt anyway.

They are driven not by ideology, but by self-preservation. Conflict is avoided. Risk is minimized. As long as they do not stand out, they believe the system will pass them by. They want to protect their livelihoods, reputations, families, and social standing. In nearly every respect, they are psychologically normal. The danger lies precisely there. Over time, they quietly recalibrate their behaviour to fit pathological conditions.

Unlike the spellbound, adapted conformists do not imagine themselves as part of a grand moral mission. Their compromises are small and incremental. Silence is reframed as prudence. Compliance becomes professionalism. They tell themselves they are “just doing their job,” that it is “not their responsibility,” or that resistance would change nothing anyway. These justifications allow them to preserve a positive self-image while gradually surrendering their conscience.

Totalitarian systems cannot function on radicalism alone. They depend on quiet cooperation—on people who keep institutions running, staff bureaucracies, follow procedures, and make repression appear routine. The adapted conformists supply continuity, legitimacy, and normalcy. Without them, the system stalls. With them, it endures.

Historical examples: Soviet factory managers, Eichmann-era German civil servants, Stasi officers, CCP teachers.

Pop-culture analogues: Winston Smith (1984), Capitol bureaucrats (The Hunger Games), Ministry of Magic officials (Harry Potter), Vault-tec employees (Fallout)

6. The Bystanders

Type: Passive majority

Driver: Fear, confusion, disengagement

Tool: Silence

Danger: Scale

Failure mode: Regret after normalization

Bystanders are not enablers in the bureaucratic sense. They do not administer the system or actively enforce its rules. Their role is quieter and more common. They are the confused, the disengaged, the overwhelmed, and the afraid. Not ideologues or functionaries, but the passive majority.

They often suffer from political fatigue and moral uncertainty. Rather than forming independent judgments, they rely on authority, social consensus, or prevailing narratives to define reality for them. Many sense that something is wrong, but lack the clarity, confidence, or energy to respond. More often than not, daily distractions—comfort, entertainment, routine—crowd out attention to what is unfolding around them.

When discomfort breaks through, it is quickly neutralized. They tell themselves that “both sides are bad,” that they “just want to live their life,” or that events “don’t really affect them.” The regime does not require their belief. It requires only their disengagement. Apathy, not conviction, is sufficient.

Over time, the abnormal becomes familiar. What once shocked becomes mundane. Silence becomes habit. Bystanders adapt not because they approve, but because resistance feels confusing, futile, or personally risky. In this way, inaction quietly clears the path for everything else to proceed.

Historical examples: the vast majority of populations under authoritarian systems.

Pop-culture analogues: the civilians caught between heroes and villains.

7. The Resisters

Type: Moral minority

Driver: Conscience over safety

Tool: Refusal

Danger to system: Exposure

Failure mode: Isolation

Resisters are the people most imagine themselves to be—and the fewest ever become. They are rare not by accident, but by design. Pathological systems move quickly to isolate them. Resisters are not defined by victory, popularity, or even success. They are defined by refusal—the refusal to internalize a lie or accept moral defeat. They are not necessarily rebellious, violent, or ideological. More often, they are simply individuals who retain moral clarity under sustained pressure.

Their defining traits are the capacity for independent judgment, the ability to endure social isolation, and a strong internal locus of control. Most are grounded in a moral framework that predates the system itself—religious conviction, philosophical reasoning, or hard-earned personal experience. Their identity is anchored in universal principles rather than group approval, which makes them difficult to assimilate and impossible to fully control.

Resisters are targeted early because they pose a symbolic threat. Totalitarian systems depend on the illusion of consensus. The mere existence of visible dissent exposes the lie that “everyone agrees.” As a result, resisters are censored, discredited, caricatured, and scapegoated. Silencing them is preventative, not reactive.

Popular culture often romanticizes resistance. Reality is harsher. Resisting a totalitarian system usually costs status, career, financial security, social belonging, and invites legal or institutional pressure. Many lose everything the average person is taught to value. What they retain—often at great personal cost—is their conscience.

Historical examples: Aleksander Solzhenitsyn, Vaclav Havel, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Edward Snowden, Galileo Galilei.

Pop-culture analogues: Katniss Everdeen (The Hunger Games), Dumbledore’s Army (Harry Potter), Neo (The Matrix), Sarah Connor (The Terminator), Aragorn (The Lord of the Rings), V (V for Vendetta).