MAiD in Canada: How Canada Became a World Leader in State-Sanctioned Death

In the quiet suburbs of Caledon, Ontario, Margaret Marsilla’s world shattered on a day that should have been like any other. Her son, Kiano was just 26 years old—a young man grappling with type 1 diabetes, partial blindness in one eye, and a long history of mental illness, including depression. Kiano had his challenges, but he also had dreams, family, and a life ahead of him. Yet, in November 2025, he traveled to British Columbia and ended his life through Canada’s Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) program, a system designed to offer compassionate relief to those in unbearable suffering.

Marsilla alleges it was wrongful euthanasia, claiming her son was not terminally ill and that his mental health “obsession” with MAiD clouded his judgment. “He had his whole life ahead of him,” she told reporters, her voice breaking with grief and outrage. She disputes the approval, which cited his blindness, diabetes, and severe peripheral neuropathy as qualifying conditions—conditions she insists were manageable and not grounds for death.

Kiano’s story began years earlier, in 2022, when he first sought MAiD approval in Ontario. A doctor initially greenlit the procedure but backed out amid public backlash after Marsilla went public with her concerns. Undeterred, Kiano persisted, finding a loophole in the system by crossing provincial lines to British Columbia, where assessments can differ. Marsilla believes the program exploited a “grey area,” approving him based on physical ailments intertwined with his mental health struggles, even though MAiD expansion for sole mental illness isn’t set to take effect until 2027. She has filed complaints and is calling for a complete overhaul of the program, arguing that safeguards failed her son. “This is disgusting on every level,” she said in interviews. Kiano’s death wasn’t just a personal loss; it highlighted how MAiD, once framed as a rare mercy for the terminally ill, has evolved into something far more accessible—and, critics argue, dangerously permissive.

A Growing Concern

Kiano’s case is not isolated. It echoes a growing chorus of concerns about MAiD’s rapid expansion and the human stories caught in its web. Consider the heartbreaking account of an Ontario woman in her 80s, referred to only as “Mrs. B” in a 2024 report from the Ontario MAiD Death Review Committee. Mrs. B had undergone coronary artery bypass graft surgery and was in decline, receiving palliative care at home under her husband’s watch. She initially expressed interest in MAiD to her family, prompting her husband—exhausted from caregiver burnout—to contact a referral service. The next day, a MAiD practitioner assessed her. But in that meeting, Mrs. B changed her mind. Citing her personal and religious beliefs, she explicitly withdrew her request, opting instead for inpatient palliative or hospice care.

What followed was a whirlwind of assessments that defied the woman’s stated wishes. Her husband, overwhelmed, took her to the emergency department the following morning, but she was discharged as stable. A palliative care doctor tried to secure hospice placement, only to be denied because she didn’t meet “end-of-life” criteria. Long-term care was offered as an alternative, but the husband pushed back, contacting the MAiD coordination centre for an “urgent” reassessment. A second practitioner deemed her eligible. The original assessor raised alarms about the rush, the sudden shift in end-of-life goals, and potential coercion from the husband’s burnout. Despite these red flags, a third virtual assessment sealed her fate, and Mrs. B was euthanized that evening—less than 48 hours after withdrawing her consent.

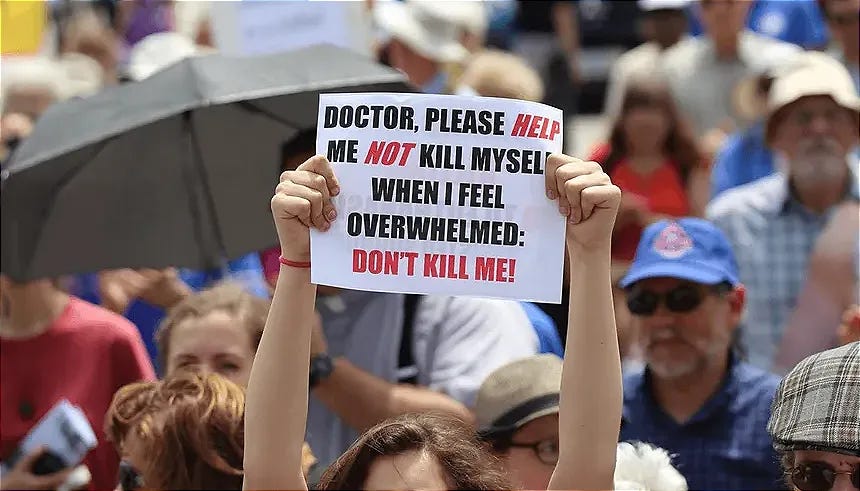

The review committee’s report painted a damning picture: the timeline was too short to explore her social circumstances, care needs, or alternatives. Most members saw no clinical urgency for same-day euthanasia and worried about external pressures, like limited palliative access and the ease of arranging MAiD over other supports. Conservative MP Rachael Thomas called it “murder,” while others questioned if it bore hallmarks of coercion. Mrs. B’s story underscores a systemic flaw: in a program meant to empower choice, vulnerability can tip the scales toward death when life-affirming options are harder to access.

The Rise of MAiD in Canada

These individual tragedies point to a broader, more insidious trend in Canada’s MAiD landscape. What began in 2016 as a limited option for adults with grievous, irremediable conditions—following the Supreme Court’s Carter v. Canada ruling—has ballooned into the world’s most expansive euthanasia regimes. Initially restricted to those whose natural death was “reasonably foreseeable” (Track 1), the program expanded in 2021 via Bill C-7 to include Track 2 cases, where death isn’t imminent but suffering from disabilities or chronic conditions is intolerable. This shift opened the door for people like Kiano, whose physical ailments intersected with mental health issues.

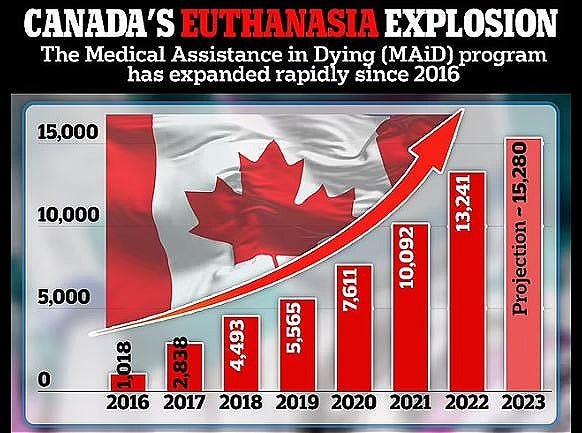

The numbers tell a story of explosive growth. In 2016, MAiD accounted for just 1,018 deaths. By 2019, it had risen to 5,565, representing 2.0% of all deaths. The surge accelerated during the COVID-19 era: 7,611 in 2020 (2.5%), 10,092 in 2021 (3.3%), 13,241 in 2022 (4.1%), 15,343 in 2023 (4.7%), and 16,499 in 2024 (5.1%). While the annual growth rate has slowed—from peaks of 36.8% between 2019-2020 to 6.9% between 2023-2024—the absolute numbers are staggering: since legalization, 76,475 Canadians have died via MAiD, making it the sixth leading cause of death nationwide, surpassing cerebrovascular diseases and rivaling some chronic conditions.

Track 2 cases, in particular, have seen sharp increases: from 224 in 2021 to 469 in 2022, 625 in 2023, and 732 in 2024—now comprising 4.4% of all MAiD deaths. These recipients are often younger, with a median age of 75.9 years compared to 78.0 for Track 1, and disproportionately women (53% of Track 2 vs. 47% of Track 1). Underlying conditions vary: cancer remains the most cited (63.4% overall), followed by cardiovascular diseases (16.3%), respiratory issues (12.1%), and neurological disorders (10.7%). In 2024, 64.1% of Track 1 and 67.7% of Track 2 recipients who self-reported disabilities required support services, highlighting how MAiD intersects with societal failures in accessibility and care. Provinces show stark disparities: Quebec leads with 5,717 deaths in 2023-2024 (7.3% of all fatalities there), followed by British Columbia (2,881 in 2024, 5.5%) and Ontario (3,962 in 2024, 3.2%). Smaller provinces like Newfoundland and Labrador lag at 1.5%.

MAiD By Default

But the statistics mask deeper controversies. Reports from oversight bodies reveal troubling patterns: in British Columbia, 22 referrals to law enforcement between 2019 and 2023 for violations like incomplete documentation or ineligible approvals. Quebec documented 16 noncompliant deaths in 2023-2024 alone. Leaked documents from Ontario’s chief coroner cited 428 unlawful MAiD cases from 2018 to 2023, including patterns of noncompliance by providers. Court injunctions in British Columbia and Alberta have questioned approval procedures, and a Quebec coroner ordered a public inquiry into a quadriplegic man’s death after he developed a bedsore from substandard care and opted for MAiD.

Critics argue MAiD has morphed from a “last resort” into a default option amid systemic shortcomings. Stories abound of veterans offered euthanasia instead of housing ramps, or disabled individuals choosing death due to poverty and lack of support. In 2024, a 53-year-old Alberta woman sought MAiD amid psychiatric distress from medication withdrawal; another case involved a man euthanized for hearing loss while on suicide watch. Emotional distress, anxiety, and existential suffering were reported by 58% of Track 1 and 63% of Track 2 recipients in 2024—up sharply from 2023—suggesting social isolation and perceived burdensomeness drive decisions more than physical pain. Nearly half (48.6%) felt like a burden on family, friends, or caregivers, a figure that has remained alarmingly consistent.

The pending expansion to mental illness as a sole condition, delayed until 2027, fuels fears of further abuse. Advance requests, already allowed in Quebec despite federal prohibitions (with over 1,400 dementia patients approved by September 2025), raise ethical nightmares: how can consent be verified when capacity is lost? Ontario’s review of dementia cases showed higher rates of loneliness and dignity loss among MAiD recipients, not pain.

Canada’s Place in the Global Landscape

Canada’s MAiD program doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it’s part of a global trend where euthanasia and assisted dying are legal in over two dozen jurisdictions, affecting more than 400 million people worldwide. Yet, Canada’s rapid growth and permissive framework have positioned it among the leaders—or, as critics say, the “worst”—in terms of accessibility and prevalence. By 2024, MAiD accounted for 5.1% of all deaths in Canada, surpassing rates in many peers and making it the second-highest globally behind the Netherlands—on a per-capita basis. By sheer volume, we lead by more than 65%.

Comparatively, the Netherlands, which legalized euthanasia in 2002, saw 9,068 cases in 2023 (5.4% of deaths) and 9,958 in 2024, with a steady rise from 1.9% in 1990. Belgium, another early adopter (2002), reported around 3,423 cases in 2023 (about 4% of deaths), up from 2.3% in earlier years. Switzerland, with assisted suicide since 1942 but no active euthanasia, had 965 cases in 2015, though rates are lower per capita. In the U.S., where assisted dying is legal in 11 states and D.C., rates are far lower—e.g., 0.6% in Oregon (2021) and 0.3% in California.

Quebec stands out even within Canada, with 7.3% of deaths via MAiD in 2023-2024, eclipsing the Netherlands’ national rate and earning it the title of the world’s highest percentage. This “leadership” raises alarms: while proponents praise Canada’s emphasis on autonomy, detractors point to lax safeguards compared to Belgium’s stricter reviews or the Netherlands’ regional variations. Globally, cancer dominates (60-100% of cases), mirroring Canada’s 63%, but Canada’s inclusion of non-terminal conditions via Track 2 sets it apart, fuelling debates on whether it’s pioneering compassion or normalizing death for the vulnerable.

Future Expansions: Government’s Plans and the Looming Decade of Change

Looking ahead, the Canadian government shows no signs of slowing MAiD’s evolution, with plans that could dramatically expand access over the next decade, potentially reshaping end-of-life care and sparking ethical firestorms. The most immediate change is the inclusion of mental illness as a sole qualifying condition, delayed multiple times but now slated for March 17, 2027. This follows Bill C-7’s 2021 expansions and responds to court rulings, but critics, including the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, warn of risks to vulnerable groups. The delay allows provinces to prepare protocols, but a Special Joint Committee report in 2024 deemed the system unready, citing gaps in mental health care.

Beyond 2027, explorations include “mature minors”—extending MAiD to those under 18 deemed capable—and advance requests, where individuals consent preemptively for future incapacity, like in dementia cases. Quebec already permits advance requests provincially, with 1,400 approvals by 2025, defying federal limits. The Quebec College of Physicians has floated euthanasia for infants with severe malformations, a practice limited to the Netherlands. Economic analyses project significant healthcare savings—up to $150 million annually from 2021 expansions alone—with one study estimating 16.7 million MAiD deaths from 2027-2047 if fully expanded, though officials deny cost as a motivator.

Public support hovers at 73%, but opposition grows among disability advocates and ethicists fearing coercion. Health Canada’s recent “national conversation” on advance requests signals intent to proceed, but without robust reforms, expansions risk eroding safeguards further.

Is MAiD coming for you? This question, posed in opinion pieces, captures the unease. What was sold as autonomy now risks devaluing lives deemed “burdensome.” Proponents celebrate choice and dignity, with 73% of Canadians approving the program. But the stories of Kiano and Mrs. B demand scrutiny: when death becomes easier than care, is mercy truly merciful? Canada must confront whether its program protects the vulnerable or preys on them. Overhaul isn’t just a mother’s plea—it’s a national imperative to reclaim compassion from convenience.

Makes me ashamed to call myself a Canadian! Then these complete wasted skins complain and call Alberta separatists treasonous what’s more treasonous than forcing the poor to commit suicide using neglect and abandonment so as it seems the easiest way out. More money spent on promoting Gender confusion, gay rights and abortion around the world on faux climate bullshit and lost to Liberal corruption than in support of people needing urgent healthcare? There is a special place in hell reserved for Canadian liberals!

This simply reflects the values, beliefs, mentality, God-less Canadians and their corrupt commie govmt. Look what happened to the ostriches and the farmers- the barbarism, the cruelty, the anonymous call that ruined hundreds of lives and indebted the farmers, look what happens at the hands of CRIMINAL and corrupt SPCA - they steal healthy animals, murder them, even if they are in the care of owners' vets, they extort the owners, they slander and LIE about their "seizures", etc... Canada of today is a disgrace, a shameless society, a cruel barbaric country.