Feminism and Its Consequences

An examination of how the feminization of Western institutions reshaped governance, conflict, and enforcement.

We were told that the future was going to be female.

The phrase first emerged in the early 1970s, when lesbian and feminist activists used The Future Is Female as both a slogan and a fundraising tool. Merchandise bearing the phrase was sold to support explicitly separatist political projects—efforts to imagine a social order organized apart from men and heterosexual norms. Over time, the slogan faded from prominence, surviving mostly as a historical artifact of second-wave feminism.

That changed in 2015, when Rachel Berks, a feminist graphic designer, rediscovered a 1975 photograph of an activist wearing a shirt with the slogan. Berks redesigned the image and began selling the updated version online, quickly selling out her initial run. She later partnered with the original photographer, Liza Cowan, to expand the merchandise line and formally revive the campaign. What began as a niche feminist project rapidly gained cultural momentum.

The slogan entered the mainstream when model Cara Delevingne wore it on a charity sweatshirt promoting Girl Up, a United Nations campaign. Although Berks and Cowan accused Delevingne of plagiarizing their design, the dispute over credit did little to slow the slogan’s spread. By then, The Future Is Female had become less a political provocation than a moral assertion about where society was headed.

During the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the phrase was embraced by supporters of Hillary Clinton as she campaigned against Donald Trump. It appeared on shirts, onesies, lapel pins, and hashtags, framing the race as a symbolic turning point rather than a conventional political contest. After Trump’s inauguration, Clinton delivered her first formal public remarks, declaring, “Despite all the challenges we face, I remain convinced that yes, the future is female.” The Los Angeles Times reported that the room erupted in applause.

Now it is 2025, and in many respects, we are living in that promised future. Journalism, law, medicine, academia, and much of the nonprofit and administrative world have become majority female. Women now make up the majority of college graduates and medical students and are approaching parity—or beyond—in management and professional leadership. This is not speculation; it is demographic reality.

We were told this transformation would produce more humane institutions: less conflict, greater empathy, and fairer outcomes. Instead, the results are more ambiguous. Inequality has widened rather than narrowed. Public discourse has grown more brittle, not more tolerant. Institutions increasingly punish dissent while advertising inclusion, enforce conformity while celebrating diversity, and confuse emotional safety with moral clarity.

The purpose of this essay is not to place blame solely on women. Feminization is not the product of women alone. It is a structural shift—demographic, psychological, and institutional—that both men and women have participated in and rewarded. If the experiment has been conducted, it is worth examining its results—carefully, honestly, and without sentimentality.

The Great Feminization

The patriarchy has been smashed.

It is common to think of feminization as something that happened long ago—marked by symbolic milestones such as the first woman attending law school in 1869, the first woman arguing a case before the Supreme Court in 1880, or the appointment of the first female Supreme Court justice in 1981. These moments loom large in our cultural memory, but they obscure a more consequential shift that occurred much later. As Helen Andrews argues in The Great Feminization, the true inflection point is not the pioneering woman, but the demographic tipping point—and that arrives around 2016.

That was the year law schools became majority female, followed by law firm associates in 2023. In journalism, the shift was massive. In 1974, only 10 percent of New York Times reporters were women; today, women make up roughly 55 percent of the newsroom. The Atlantic’s editorial staff was 53 percent male in 2013 and just 36 percent male by 2024. Medical schools crossed the same threshold in 2019. Women became a majority of the college-educated workforce nationwide that same year, a majority of college instructors by 2023, and now account for 46 percent of managers—on pace to surpass parity. These are not isolated cases. The pattern repeats across nearly every prestige-producing institution in the West.

Many people interpret these shifts as the natural result of “progress”—women finally competing on equal footing and outperforming men. Andrews rejects this explanation. “Feminization is not an organic result of women outcompeting men,” she writes. “It is an artificial result of social engineering, and if we take our thumb off the scale it will collapse within a generation.” The key driver is not merit alone, but incentives created by law, regulation, and institutional risk management.

Anti-discrimination law is the most obvious thumb on the scale. It is illegal to employ too few women, particularly in senior roles. Underrepresentation invites litigation, and the penalties can be catastrophic. As a result, employers rationally adjust. “Employers give women jobs and promotions they would not otherwise have gotten simply in order to keep their numbers up,” Andrews observes. Major corporations like Texaco, Goldman Sachs, Novartis, and Coca-Cola have paid significant settlements over alleged gender discrimination—some as high as $215 million. In Silicon Valley, companies have been sued over “frat boy culture” or “toxic bro culture,” reinforcing the same incentives. When failing to demonstrate sufficient feminization can cost hundreds of millions of dollars, institutional behaviour predictably follows.

Yet this system contains a profound asymmetry. As Andrews notes, “Women can sue their bosses for running a workplace that feels like a fraternity house, but men can’t sue when their workplace feels like a Montessori kindergarten.” Masculine norms carry legal risk; feminine norms do not.

Nor should we expect feminization to stabilize at “equity.” Once institutions cross the fifty-fifty threshold, they tend to overshoot, as norms change and men quietly exit. Andrews poses the obvious question: “What self-respecting male graduate student would pursue a career in academia when his peers will ostracize him for stating his disagreements too bluntly or espousing a controversial opinion?”

With the demographic transformation established, we must now understand how masculine and feminine group dynamics differ—and why those differences matter once they scale.

Gender Dynamics 101

In 2025, it has somehow become controversial to note that men and women are not identical—that they tend, on average, to exhibit different behavioural patterns shaped by biology, incentives, and social context. Yet denying these differences does not make them disappear. It merely makes their effects harder to understand.

As Western institutions undergo rapid feminization, understanding the contrast between masculine and feminine group dynamics becomes essential. This is not an argument about individual capability or moral worth. There are exceptions to every pattern, and no serious observer denies individual variation. But exceptions do not negate group-level tendencies, especially when institutions operate at scale.

Across cultures—and even across species—social psychologists and primatologists have observed consistent differences in how male and female groups organize themselves. In both humans and chimpanzees, male groups tend to orient around objectives: they focus on accomplishing the task, competing effectively, and resolving disputes clearly so cooperation can resume. Conflict is often direct, bounded, and followed by reconciliation once the goal is achieved.

Female group dynamics, by contrast, tend to prioritize cohesion and relational harmony. The quality of the social environment matters as much as—or more than—the outcome itself. Decisions are shaped by consensus, participation, and interpersonal comfort. The process must feel fair and inclusive, even if doing so comes at the expense of efficiency or decisive resolution. Success, in this context, is measured less by winning than by maintaining agreeable relations within the group.

These differences matter enormously once they are scaled into institutions. In a predominantly masculine, mission-oriented ethos, institutions are defined by clear purposes: the legal system exists to adjudicate disputes and deliver justice; academia to pursue truth through debate; business to create wealth; journalism to investigate and inform; militaries to fight and deter; borders to regulate entry. Each institution has a function that requires hierarchy, standards, and the tolerance of conflict.

Increasingly, however, these institutions are governed by a single overriding imperative: inclusion. Diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives now function as a universal mission statement, regardless of whether they align with an institution’s core purpose. Outcomes matter less than process, and success is judged by whether everyone feels represented rather than whether the institution performs its essential role.

This helps explain why so many institutions feel simultaneously busy and ineffective. Performance is secondary to atmosphere. Disagreement is reframed as disruption. And while inclusion is publicly emphasized, coalitions in practice remain selective—formed among those who share the same moral and social sensibilities.

None of this is to argue that feminine group dynamics are inherently flawed. On the contrary, they are stabilizing at the level of families and small communities, where care, cohesion, and emotional sensitivity are indispensable. The problem arises when the same dynamics are imposed on large-scale institutions designed for truth-seeking, adjudication, and enforcement—domains where clarity, standards, and the capacity to tolerate conflict are not optional, but essential.

Turning the Government Into a Daycare

In no domain has feminization proven more consequential than in governance.

For most of human history, the state’s core function was understood plainly: it existed to monopolize force, conduct war, enforce law, and maintain order. Whether monarchic or democratic, legitimate authority rested on the capacity to compel, defend, and adjudicate. Power was not denied or sentimentalized; it was acknowledged and constrained.

In the modern West, that understanding has eroded. As feminist narratives gained cultural dominance and women became the majority within many public institutions, the purpose of the state was quietly reimagined. Power itself became suspect. Force was reframed as inherently immoral. In its place emerged a new vision of governance—not as authority, but as care.

Feminine moral instincts evolved for caregiving and protection have increasingly been encoded into law and policy. Citizens are no longer treated primarily as participants in a political order, but as dependents within a managed system. The state is no longer expected first and foremost to enforce laws, defend borders, or adjudicate disputes impartially. Instead, it is asked to soothe social tensions, redistribute resources, protect feelings, and manage outcomes.

In effect, the state increasingly functions like a daycare.

This transformation is reflected in voting behaviour. In Canada, women have consistently been more likely than men to support the Liberal Party, the NDP, and the Greens, with the gender gap persisting across the last four federal elections. In the recent New York City mayoral race, exit polling showed that 84 percent of women aged 18–29 supported Zohran Mamdani’s explicitly redistributive, caretaker-oriented platform. These patterns are not abnormal. They are predictable expressions of a broader moral orientation toward governance as provision rather than enforcement.

The structural conditions reinforce the trend. As families fragment, marriages form later and dissolve more often, and fathers are increasingly absent from daily life, localized male provision declines. Politicians—particularly those ideologically hostile to the family (leftists)—step into the vacuum, promising to replace private obligation with public care. Individual responsibility is traded for bureaucratic administration. Provision is centralized. Men disproportionately fund the state, which then redistributes resources on their behalf.

The irony is profound. Women are told that reliance on men is weakness, while reliance on bureaucracy is empowerment. Yet this does not restore power to individual women, who historically exercised far greater leverage within family structures. Instead, it transfers power upward—from individual men and women alike—to an impersonal state apparatus beyond the control of either.

This is where daycare logic fully asserts itself. In a feminized state, citizens are sorted into moral categories: infants—the vulnerable and oppressed—who must be protected; caregivers and moral enforcers—“allies”—who administer the system; and predators—dissenters deemed hateful or dangerous—who must be excluded.

If the modern state feels less like a neutral arbiter and more like a suffocating mother, this is why.

The Dangers of Safety-ism

Feminized governance in the modern West has collapsed the distinction between discomfort and danger. In its place has emerged a moral framework in which safety is elevated above liberty and emotional unease is treated as evidence of harm. When a culture begins to regard speech as violence, disagreement as injury, and inclusion as the highest political good, it renders itself uniquely vulnerable to authoritarian control.

Once emotional discomfort is reclassified as harm in the minds of legislators and administrators, it follows that such harm must be prevented proactively. This logic supplies the justification for censorship regimes, hate-speech laws, speech codes, and ever-expanding regulatory oversight. Within a daycare-style model of governance, the moral logic is simple: when an “infant” (a victimized or protected class) expresses distress, a caregiver (“ally”) must intervene to neutralize any perceived predator (dissenter or nonconformist).

George Orwell recognized this psychological vulnerability long before it took institutional form. In 1984, he observed that “it was always the women, and above all the young ones, who were the most bigoted adherents of the Party, the swallowers of slogans, the amateur spies and nosers out of unorthodoxy.” Orwell was not making a misogynistic claim, but a psychological one. The maternal instinct to prioritize safety and compassion over risk and freedom—essential and stabilizing in the family—can be weaponized at scale by totalitarian systems. Propaganda reframes conformity as kindness and control as care, tapping into moral intuitions that feel virtuous even as they justify coercion.

This dynamic also produces a secondary effect. If the state succeeds in training women to interpret tyranny as protection, a subset of men will follow. Men who lack status or competitive advantage increasingly adapt by adopting the moral language and postures favoured in feminized environments. Evolutionary psychologists describe this as a “sneaky fucker” strategy: rather than competing directly, some men mimic the values and behaviours rewarded by dominant moral coalitions, seeking social or romantic access through ideological alignment instead of achievement. Feminized political spaces offer environments where status is conferred by moral signalling rather than competence or risk-taking.

The result is a coalition of risk-averse moral enforcers—women and compliant men alike—applauding the steady erosion of civil liberties in the name of safety. While it is reasonable for governments to protect citizens from genuine threats, a feminized moral ethos lowers the threshold for danger so dramatically that almost anything can qualify. Intervention becomes perpetual.

The episode surrounding former Harvard president Larry Summers illustrates this perfectly. When Summers suggested that sex differences in aptitude and preference might partly explain female underrepresentation in certain STEM fields, his remarks were treated not as debatable claims but as existential harm. MIT biologist Nancy Hopkins responded, “When he started talking about innate differences in men and women, I just couldn’t breathe because this kind of bias makes me physically ill.” That reaction captures the logic of safetyism: words are not merely offensive; they are physically dangerous.

If words are treated as contagious threats, then the only consistent response is a lockdown on thought. Once this emotional framework is accepted, totalitarian outcomes are no longer extreme—they are logical. Persuasion becomes indistinguishable from assault. Debate becomes a form of violence. Institutions adapt accordingly with human resources departments assuming inquisitorial roles, speech codes and safe spaces proliferating, as well as deplatforming becoming routine.

Here lies the central paradox of safetyism: the more safety is prioritized, the more fragile the culture becomes. Conflict is not eliminated—it is suppressed, moralized, and ultimately intensified. A society that cannot tolerate discomfort cannot correct error, sustain pluralism, or preserve freedom for long.

Feminizing Conflict

The greatest myth advanced by modern feminism is that a female-led society would be more tolerant and less prone to conflict. The evidence points in the opposite direction.

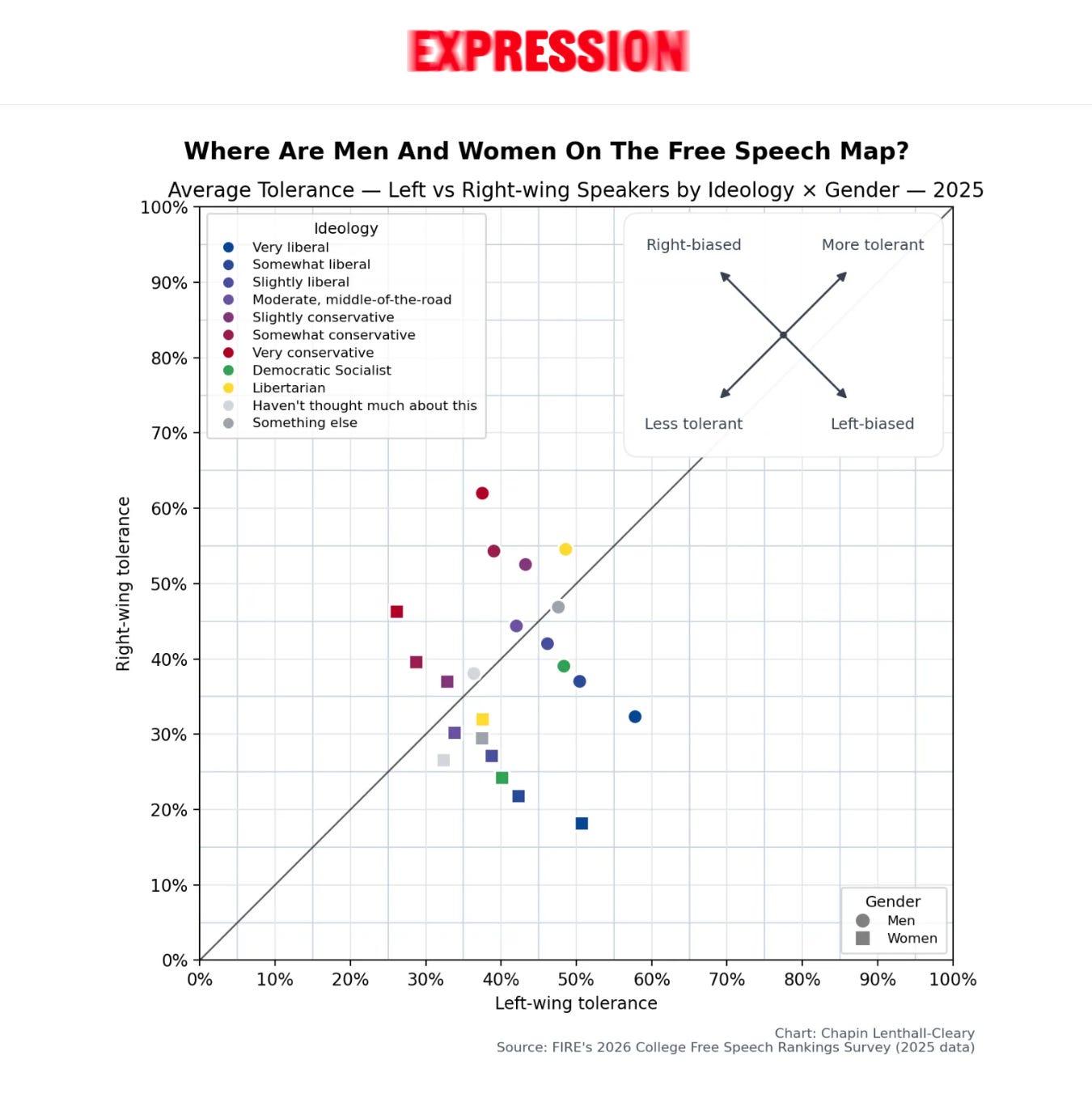

Recent data from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) shows that, across nearly every ideological category, men score higher in tolerance for both left- and right-wing speakers. Women, by contrast, score lower overall and display particularly strong hostility toward right-leaning speech. In practical terms, this means that men—regardless of political affiliation—are, on average, more tolerant of dissent than women across the political spectrum.

There is only one notable exception: men who report having little interest in or knowledge of politics also score poorly on tolerance. Ignorance and insecurity, not masculinity, appear to be the primary drivers of intolerance. Where confidence and competence are present, tolerance increases; where they are absent, repression follows.

These modern findings align closely with long-standing observations in primatology. In Chimpanzee Politics, Frans de Waal documents that female chimpanzees are frequently involved in conflicts without engaging in direct physical aggression. Rather than fighting themselves, they influence outcomes through screaming, gesturing, and aligning with particular males. Male intervention, de Waal notes, is often triggered by female distress signals, and some females are markedly more effective than others at mobilizing male support. Conflict, in other words, is not avoided—it is initiated indirectly and enforced by proxies.

De Waal further observes a crucial difference in resolution. Male conflicts, even when intense, tend to end with reconciliation once dominance relationships are clarified. Female conflicts, by contrast, are more likely to persist without clear resolution, involving ongoing social competition rather than decisive confrontation. The absence of reconciliation means that grievances linger and hostility hardens over time.

This same pattern appears in human political history. A large-scale historical analysis of European monarchies by Oeindrila Dube and S. P. Harish finds that polities ruled by queens were more likely to engage in war than those ruled by kings. The effect varies by marital status: unmarried queens were more likely to be attacked, while married queens—those with access to male military and political support—were more likely to participate as aggressors and to fight alongside allies. Female leadership did not reduce conflict; it reshaped the conditions under which conflict occurred.

The illusion of female pacifism persists because conflict is often displaced rather than eliminated. When confrontation is indirect and enforcement is delegated, aggression becomes less visible but no less real. Feminized systems appear peaceful only because the fighting is done through intermediaries—institutions, coalitions, reputational punishment, or male enforcers—rather than through open confrontation.

Conflict does not disappear in feminized societies. It becomes more common but less significant. It is moralized, outsourced, and prolonged—rendered less honest, less resolvable, and ultimately more corrosive to social trust and institutional stability.

Force Doctrine and the Dependency Paradox

Every political order, no matter how compassionate its rhetoric, rests on force. Laws are not self-executing. Rights do not enforce themselves. Borders do not defend themselves. Behind every statute, court ruling, and social guarantee lies the credible threat of force. Civilization does not eliminate violence; it disciplines it.